African Cooking

African Cooking

My Continent: A Personal View - Section 1 of 8 (1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 )

My earliest memories of Africa, and of my life there, center around the large dining table in the home of my Boer grandfather, in the Orange Free State, deep in the interior of South Africa. And almost invariably the scene in this theater of my past is the evening meal. I used to wait for this meal, six decades ago, with the same kind of excitement that I was to experience much later as a drama critic in London, before the curtain rose on the first night of a new work by a friend from whom I expected much. As in a darkened playhouse, the excitement would start when the maids began to light the heavy oil lamps in the long passage that led from the front door on the veranda surrounding the house. At last they came into the dining room, and the biggest lamp of all. In the center of the room was a great table made of an African wood so hard and so dense that a piece would sink like iron if it was thrown into water; and over the center of the table, suspended in massive chains from the ceiling, hung an immense oil lamp made of brass that glowed and shone like gold. It took a servant several hours to polish that lamp once a week, and to me it always looked like the sort of lamp that Solomon in all his glory might have hung in his first temple in the Promised Land.

As the 13th of 15 children, I used to stare at the lighting of this lamp as one might witness a miracle. I would watch the shadows roll back into the recesses of the heavy old Dutch furniture and see the lamplight fall, as in a painting by Rembrandt, on the table waiting for its full complement of family and guest. At the same time I would become aware of a subtle scent of spice drifting into the dining room from the kitchen.

The sense of smell is surely the most evocative of all our senses. It goes deeper than conscious thought or organized memory and has a will of its own that the mind is compelled to heed. Since the scent of cinnamon is the first to present itself to my memory of the moment when the great lamp was lit and the great table set and ready, I must accept the fact that my first coherent recollection of the drama of our evening meal begins with the serving of a typical milk soup of the South African interior. What is more, on the nights I remember, it must have been freezing outside because we children only had this soup only in winter. I am all the more sure of this because my grandfather and the black ladies that cooked for him knew that there was nothing that pleased young palates more than a milk soup.

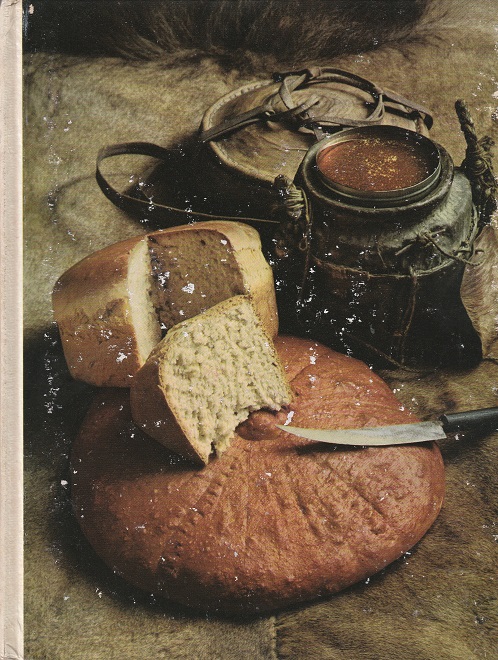

Made with the simplest of ingredients, the soup went under the name of snysels, which may be translated as "slicings" - in this case, "slicings" of a homemade pasta consisting of wheat flour mixed with egg, rolled out as thin as possible, and cut into fine strips. These strips were tossed into a large cast-iron pot of boiling milk, already sugared and richly spiced with sticks of cinnamon. When the strips of pasta rose to the surface, semitransparent but still firm to the tooth, the soup was ready for serving. It would be borne into the dining room in a cloud of aromatic steam, filling the air with that incomparable and unforgettable scent of cinnamon that, more than any other spice, seemed to us the quintessential emanation of the Far East.

The fragrance of cinnamon would still be adrift in the room when more acute scent of cloves announced that the main course was on its way. This would be a superbly pot-roasted leg of lamb, a standard dish of the interior. Studded with cloves from Zanzibar, less than 2,000 miles from us as the crow flies, the lamb - itself a product of our farm - was so tender that it seemed to flake rather than cut at the touch of my grandfather's carving knife.

Section Break